You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘FYP’ tag.

Xi Jinping departed Moscow eight days ago following his three-day state visit. In broad brush, the trip removed some uncertainties about the basic direction of Xi’s positioning on the global stage. No, this was not a peace-broker’s mission. Xi clearly prioritized propping up a faltering “friend without limits” over any serious — or even half-hearted — effort to play the honest broker. Washington and Kyiv still want Xi to talk with Zelensky (likely) or perhaps even visit Kyiv (unlikely) but the aim is not for any mediation by Xi but rather to reinforce the messaging to Xi about not sending lethal armaments to Russia. And, no, Xi seems quite clearly to be prioritizing the recovery of his wobbly economy over the risk of sanctions from the U.S., Europe and key Asian partners should he defy the Biden Administration red-line against China supplying Russia with lethal armaments.

As the third door opens, it’s now possible to glimpse some of the finer brush-strokes of Xi’s long-term plan to counter the liberal, rules-based world order. These are revealed in the 9-point joint statement released by Putin and Xi at the conclusion of Xi’s Moscow visit as well through related moves by China on the world stage. Five of the more subtle brush-strokes to observe:

- Xi used his trip to signal to Washington and to NATO and its other democratic allies that China now largely has Russia under its thumb. It can draw increasingly on Russia as a plentiful supply of heavily-discounted oil and other energy resources. Similarly, it can address its own food insecurity and inflation concerns by throwing its market open to Russian food commodities at cut-rate prices. It can force Russian banks and the Russian financial system to do its bidding (see next point). And it can count on Russia to parrot its propaganda line with particular focus on Africa, South America and the Pacific region. All of this serves to prop up Putin and prolong the war, serving Xi’s interests without triggering retaliation against China.

- Xi revealed that his weapon of choice to counter the post-WWII world order will not be lethal armament deliveries to Moscow but the Chinese yuan (RMB, renminbi). Moreover, he put the brush in Putin’s hand for this particular stroke. Towards the end of the summit, Putin pointedly stated “We (Putin and Xi) are in favor of using the Chinese yuan for settlements between Russia and the countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America.” From a broad strategic perspective, it makes perfect sense that Xi would choose this approach. Why risk retaliation by getting involved in a hot war in Europe (where Russia is losing ground), when China can force Russia to support a Chinese-led challenge to U.S. dollar domination elsewhere throughout the world. The standing of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency is arguably the United States’ most potent, non-military asset globally. Others have tried to dislodge it and have failed. But, as the world’s second largest economy, as the de facto leader of the developing world for the past 50 years, and as a vise-grip political command structure, Xi clearly sees this approach as his best bet for now (while the Taiwan issue still hangs unresolved in the background).

- Putin’s statement comes not as an announcement of any new undertaking by Xi but rather as an exclamation point on an ever-evolving geo-strategic campaign which Xi has been conducting in Asia, Africa and Latin America since 2012 in the form of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). There is particular urgency to this campaign now in the wake of the COVID pandemic and the recent rapid rise in U.S. interest rates. As a result of these developments, many BRI partner/client countries now find themselves unable to service their earlier loan obligations to China. To adjust, China has been forced to dramatically increase its overall lending through loan restructurings to keep major BRI projects afloat. As a result, Chinese lending to debt-ridden countries now stands at more than $40 billion, not far off the level of the traditional, post-WWII lender of last resort, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose loan exposure stands at more than $65 billion. While a strain on PRC finances, this hefty lending posture gives Xi the ability to speak softly (through Putin) while carrying a big stick against the dollar-denominated international order.

- China’s burst of Mid-East diplomacy is a further brush-stroke filling out this picture. The opportunistic stage-craft positioning PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi as the go-between in the mid-March entente between Saudi Arabia and Iran — which was happening anyhow — was meticulously executed. Likewise, the bullhorn which the Foreign Ministry has used to welcome the possibility of rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Syria is notable. All of this is leading up to a summit between Iran and the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council in Beijing in the fall. Against the broad backdrop of events, it is certainly not a coincidence that Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s leader, has been mentioning under his breath the possiblity of settling more of his country’s oil exports with the Chinese yuan.

- A final point is the deep planning behind what is now unfolding. None of this reflects ad hoc or reactive moves in response to the Ukraine crisis. Instead, this plan is organically tied to the development of the ten-year-old Belt and Road Initiative and signs of it became clearer with the convening of the 20th Party Congress last October, with the unveiling of the CCP’s newest Five Year Plan (FYP) and with the announcement of the country’s new ministerial line-up at the Two Sessions meetings in Beijing earlier this month. In hindsight, the strongest proof of this is in the meeting just concluded with Putin. Ukraine was just a minor, slightly discomfiting blip for Xi in Moscow last week, just as it was only a blip for Xi when Putin invaded Ukraine just days after their meeting in Beijing in February 2022 on the eve of the Olympics. Xi is extolled in China as being “unswerving.” At least as far as his plan to offer an alternative world order is concerned, this characterization is apt. No swerving from the plan just because of an unprovoked invasion of a sovereign nation by his Russian friend. As Alexander Korolev’s (University of New South Wales) observed regarding the Xi-Putin 9-point joint statement: “It looks like a strategic plan for a decade or even more. It’s not a knee-jerk reaction to the war in Ukraine.” Fits in well with the three 5-year chapters through which Xi has been telling his heroic ‘rejuvenation of China’ story. A story that can’t end well for Xi without closing the book on Taiwan.

I received an email yesterday from a college friend who is bright, informed and engaged with world events. She is not a China specialist but over the last few years we have had an on-going exchange of views about China, both privately and in a public forum.

Her message from yesterday read,”Terry: Yikes. Do you have access to Le Monde? I can’t read the rest of the article, but the first half is alarming. R.” The article she hyperlinked is from Le Monde and that article in turn hyperlinks to a strategy document which the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has just released in conjunction with the visit by Wang Yi, Xi Jinping’s principal foreign policy advisor, to Munich for the 59th Munich Security Conference with NATO member countries and then on to Russia for meetings with Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and yesterday with Putin himself. The document is titled “American hegemony and its dangers.” As headlined — accurately, I might add — in the Le Monde article, the focus of Xi’s Foreign Ministry is now on “‘direct confrontation with the United States.”

Today’s brief post is both my response to her and a way of brushing off the cobwebs after a long holiday vacation — lasting from Thanksgiving through Chinese New Year — I have taken from Assessing China.

To keep it simple, there are two main reasons that this newly overt stance of direct confrontation with the U.S. comes as no surprise from Xi’s PRC in 2023.

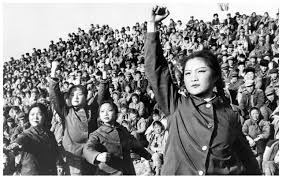

The first goes back as far as 1921 with the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Shanghai. Inspired by the Bolsheviks’ gains in the October Revolution, Chen Duxiu and other founding leaders of the CCP made Leninist ideology (soon to become Leninist-Stalinist ideology after Stalin’s rise to power in 1924) the central tent-pole of the party. According to that ideology, the bases of CCP power were the Three P’s — the Party, the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) and propaganda. Since seizing the mainland and ousting Chiang Kaishek’s rival Kuomintang Party in 1949, the centrality of this ideology has only been tested twice. The first was the slow-boil Sino-Soviet split which began in 1956 and culminated in 1972 when China turned its back on its Big Brother in Communist ideology and welcomed Richard Nixon. The second came with the introduction of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms which started experimentally in 1978 and were formally adopted in 1982.

The effect of these reforms was monumental. For the first time since 1921, decision-making within the CCP was to be based on a predictable economic logic and not on malleable political ideology. It ushered in a 30-year period of economic growth which according to the World Bank has lifted 800 million people out of poverty. Western observers, myself included, tended to assume that this three decade burst of wealth creation under the post-WWII Pax Americana would be enough to make PRC leadership want to become a permanent “stakeholder” in this global order. In hindsight, we underestimated the strength of the CCP’s ideological ‘muscle memory,’ of its basic political motivation and of China’s civilizational pride (and resentments). What is a seventy-five year Post-WWII order measured against a four thousand year civilizational record in which the Peoples’ Republic of China is, in cultural terms, its latest dynasty. And, as Orville Schell has masterfully made the case in Wealth and Power, not even Deng Xiaoping probably ever saw wealth-creation for China in a Washington-led world order as an end in itself, but rather as a step toward global power that would enable China to challenge that world order in due course. For Xi Jinping, a true ideologue inspired by his father’s revolutionary experience, that time is now.

Secondly, the path that China has been taking to overt confrontation with the West has been revealing itself in planned and increasingly obvious stages ever since 2008. 2008 was the year of the Global Financial Crisis, which China weathered with less turmoil and damage than the advanced economies in the West and Asia. That is the year that CCP leadership started taking stock of what it had gained in capital accumulation and talent acquisition and began thinking about striking out on its own different path. There was still a need to access Western consumer and financial markets and to promote inflow of management expertise along with inbound investment but the critical need was technology. In 2008, China was in no position to compete with the West and Western-aligned countries like Japan, Taiwan and South Korea in advanced technology. For that reason, over the next fifteen years, CCP ambitions were always partially cloaked but increasingly revealed with each Five Year Plan cycle. (See Xi’s Ascension to the CCP Pantheon for a more detailed mapping of that 15-year course). In 2012, the CCP selected Xi Jinping as the horse they would ride on this epochal journey. He would break the mold which Deng Xiaoping had set limiting Chinese leaders to two five-year terms. And he would use his longer leash to bring Hong Kong and Taiwan to heel before stepping down. To usher in the next Five Year cycle of the Politburo in 2017, Xi gave a triumphalist speech telling the world what to expect in the years ahead. Now, fresh from securing an unprecedented third term of formal power last year, Xi is moving to make those stated intentions a reality. The pandemic and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and Biden’s CHIPS Act were not part of the plan. But Xi and the CCP are ‘unswerving’ in pushing forward with this plan. It has been fifteen years in the making and, for much of it, the U.S. and its allies have been distracted in the Middle East and Ukraine. With its population now in decline, Xi knows the window is closing for him to reshape the global order to his and the CCP’s liking.

With ‘ideology in command’ and riding fifteen years of planning momentum, China’s direction under Xi is now clear for all to see. Xi’s strategic accommodation with junior partner (and client-state energy supplier) Russia last February was simply another way-station on its path. The path to open confrontation with the leaders of the post-WWII order, and the scramble for influence with less tightly aligned global players like Brazil, Hungary, Turkey, South Africa, India and Indonesia, is afoot.

Autocracy vs Democracy. Game on.